College Learning – Strategies for Student Engagement and Success

Reading

GOALS

We all have goals, things we are aiming for in our future. College students want to be academically successful, moving closer to their future careers. But how can we make that happen? What steps do we need to take to achieve our desired results? Setting goals and working towards achieving those goals will play a big part in being successful in college. Goals give us a focus on what we want to accomplish and allow us to measure our success.

Goals can relate to a variety of aspects of our lives. We can have goals related to academics, family, health, social, financial, etc. The focus of the goals related to college may seem like they only related to academics, but many of our goals may overlap in more than one of these categories.

How To Start Reaching Your Goals

Without goals, we aren’t sure what we are trying to accomplish, and there is little way of knowing if we are accomplishing anything. If you already have a goal-setting plan that works well for you, keep it. If you don’t have goals, or have difficulty working towards them, we encourage you to try this.

Make a list of all the things you want to accomplish for the next day. Here is a sample to do list:

- Go to grocery store

- Go to class

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Social media

- Study

- Eat lunch with friend

- Work

- Watch TV

- Text friends

Your list may be similar to this one or it may be completely different. It is yours, so you can make it however you want. Do not be concerned about the length of your list or the number of items on it.

“Obstacles are things a person sees when he takes his eyes off his goal.”

– E. Joseph Cossman

You now have the framework for what you want to accomplish the next day. Hang on to that list. We will use it again.

Now take a look at the upcoming week, the next month and the next year. Make a list of what you would like to accomplish in each of those time frames. If you want to study abroad, visit a new city or state for leisure, or get a bachelor’s degree, write it down. Pay attention to detail. The more detail within your goals the better. Ask yourself this question: what is necessary to complete my goals?

Goal Setting

Now that you have a list of your short-term goals (next day) and long-term goals (next week, month, year), let’s take into consideration how the best goals are created.

One common tool for effective goal setting is developing SMART goals.

- Specific – A project needs to be specific about what it will accomplish. Unlike many organizational goals, the goal of a project should not be vague or nebulous. An organization may want to ‘make London, Ontario a great place to live’, but its projects need to focus on a specific goal. For example, a more specific goal would be to build a downtown farmers’ market. A project that is specific is one that can be clearly communicated to all team members and stakeholders. A specific project goal will answer the five ‘W’ questions:

- What do we want to accomplish?

- Why are we undertaking this project?

- Who is involved or will be affected by the project?

- Where will this project be conducted?

- Which constraints (scope, time, money, risk, etc.) have been placed on our project?

- Measurable – How will project progress and success be measured? What will be the measurable difference once our project is completed successfully? These measures should be quantifiable.

- Assignable – Who will do the work? Can people be identified who have the expertise in the organization to complete this work? Or can the expertise be hired from outside of the organization?

- Realistic – Is it realistic that the organization can achieve this project, given its talents and resources? This is a very important consideration for businesses of all sizes. Yes, it would be great to produce a new driverless car, but is that realistic given the resources that the organization has available?

- Time-related – when will the project be completed and how long will it take? These criteria can be very useful when defining a project. If the description for a project does not meet all these criteria, then it is time to go back to the drawing board and make sure that what is being described is really a project, rather than a program or strategic goal.

Are your goals SMART goals? For example, a general goal would be, “Achieve an ‘A’ in my anatomy class.” But a more specific, measurable, and timely goal would say, “I will schedule and study for one hour each day at the library from 2pm-3pm for my anatomy class in order to achieve an ‘A’ and help me gain admission to nursing school.” Whether goals are attainable or realistic may vary from person to person.

Now revise your lists for the things you want to accomplish in the next week, month and year by applying the SMART goal techniques. The best goals are usually created over time and through the process of more than one attempt, so spend some time completing this. Do not expect to have “perfect” goals on your first attempt. Also, keep in mind that your goals do not have to be set in stone. They can change. And since over time things will change around you, your goals should also change.

Another important aspect of goal setting is accountability. Someone could have great intentions and set up SMART goals for all of the things they want to accomplish. But if they don’t work towards those goals and complete them, they likely won’t be successful. It is easy to see if we are accountable in short-term goals. Take the daily to-do list for example. How many of the things that you set out to accomplish, did you accomplish? How many were the most important things on that list? Were you satisfied? Were you successful? Did you learn anything for future planning or self-management? Would you do anything differently? The answers to these questions help determine accountability.

Long-term goals are more difficult to create and it is more challenging for us to stay accountable. Think of New Year’s Resolutions. Gyms are packed and mass dieting begins in January. By March, many gyms are empty and diets have failed. Why? Because it is easier to crash diet and exercise regularly for short periods of time than it is to make long-term lifestyle and habitual changes.

SMART GOALS PRACTICE

Begin to set your learning goals for this semester. Choose one goal and use the SMART goal system to check that your goal is relevant and achievable. Click here to download a printable worksheet for this activity.

| Specific

|

|

| Measurable

|

|

| Attainable

|

|

| Relevant

|

|

| Time-bound

|

Break Goals into Small Steps

If we decided today that our goal was to run a marathon and then went out tomorrow and tried to run one, what would happen? We might respond with: (jokingly) “I would die,” or “I couldn’t do it.” How come? Because we might need training, running shoes, support, knowledge, experience and confidence—often this cannot be done overnight. An academic goal might be obtaining an A grade on a mid-term essay for a writing class. Small steps might include getting started, planning time for smaller tasks, researching, writing a draft, visiting a writing support service, having a friend proofread, revising. Instead of giving up and thinking it’s impossible because the task is too big for which to prepare, it’s important to develop smaller steps or tasks that can be started and worked on immediately. Once all of the small steps are completed, you’ll be on your way to accomplishing your big goals.

What steps would you need to complete the following big goals?

- Buying a house

- Finding a long term partner

- Attaining a bachelor’s degree

- Attaining an associate’s degree

Prioritizing Goals

Why is it important to prioritize? Let’s look back at the sample list. If we spent all my time completing the first seven things on the list, but the last three were the most important, then we would not have prioritized very well.

It would have been better to prioritize the list after creating it and then work on the items that are most important first. You might be surprised at how many students fail to prioritize.

After prioritizing, the sample list now looks like this:

- Go to class

- Work

- Study

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Eat lunch with friend

- Go to grocery store

- Text friends

- Social media

- Watch TV

One way to prioritize is to give each task a value. A = Task related to goals; B = Important—Have to do; C = Could postpone. Then, map out your day so that with the time available to you, work on your A goals first. You’ll now see below our list has the ABC labels. You will also notice a few items have changed positions based on their label. Keep in mind that different people will label things different ways because we all have different goals and different things that are important to us. There is no right or wrong here, but it is paramount to know what is important to you, and to know how you will spend the majority of your time with the things that are the most important to you.

A Go to class

A Study

A Exercise

B Work

B Pay bills

B Go to grocery store

C Eat lunch with friend

C Text friends

C Social media

C Watch TV

Do the Most Important Things First

Spending your time on “C” tasks instead of “A” tasks won’t allow you to complete your goals. The easiest things to do and the ones that take the least amount of time are often what people do first. Checking Facebook or texting might only take a few minutes but doing it prior to studying means we’re spending time with a “C” activity before an “A” activity.

People like to check things off that they have done. It feels good. But don’t confuse productivity with accomplishment of tasks that aren’t important. You could have a long list of things that you completed, but if they aren’t important to you, it probably wasn’t the best use of your time.

Tips for Setting Goals

We have evaluated our goals and set some goals for the upcoming semester. Let’s summarize with some tips for goal setting:

- Create a mental picture so you can visualize your goals. This includes the end goal as well as the steps needed to get there.

- Make sure the goals are measurable. Remember to include a timeframe and amounts.

- Set check points for yourself to make sure you are on track.

- Know there will be challenges and think about how you will overcome obstacles.

- Be sure to share your goals with others so they can help hold you accountable.

- As things change, you may need to adjust your goals as well. Review your goals periodically to make sure they continue to be realistic and achievable.

Setting goals will give you a purpose and help you focus on what you want to accomplish during your college experience. There will be many small steps you will need to focus on along the way helping you achieve your long-term goals. Use these concepts on setting and prioritizing goals to assist you and provide the motivation you need to be successful!

TIME MANAGEMENT

There are many things calling for your time, add schoolwork to that and time management becomes even more important. With only 24 hours in a day, you get access to 168 hours a week! That may sound like a lot, but 49-56 of those hours (7-8 hours a night) are hopefully spent sleeping, leaving at most 119 hours of time awake. The first important step to time management, is find out what is taking up all your time.

Make a list of all the things you do that take up time in your day and week. Click each category below to learn more about the types of activities to consider.

Map it out!

After reviewing your time commitments map out what your week looks like, starting with things that repeat or are top priorities and then adding in the items that are more flexible. Be sure to prioritize sleeping and eating! These are important to your success in all that you do.

There are many tools to help you with organizing and evaluating your time, consider the following:

Prefer digital tools?

- Digital calendars, example: Google Calendar

- Digital planner Apps

- Digital worksheets, example: Weekly Work Sheet

Prefer paper tools?

- Printed copy of digital worksheets, example: Weekly Work Sheet

- Paper planner, example: academic agenda book

- Desk or wall calendars

Try it yourself!

Select one organization tool and plan out the next week. As you move through the week update and note any changes to your plan. At the end reflect and review what went well and what did not work out for you. Consider this as you continue to work on finding a tool that will assist you with your time management and staying organized.

Take your time management and organization to the next level:

THE BASICS OF STUDY SKILLS

“If you study to remember, you will forget, but, if you study to understand, you will

remember.”

– Unknown

Why do some students earn good grades and others do not? Answers vary. Students with poor grades have said students with good grades are born book smart. Students with good grades answer that studying and hard work got them there. What do you think? Everyone likes to earn an A grade. Despite the stigma of being a “nerd,” it feels good to receive good grades. Take pride in your preparation, take pride in your studying, and take pride in your accomplishments. Students know many things they need to do in order to achieve good grades – they just don’t always perform them.

Be Prepared for Each Class

Complete your assigned reading ahead of the deadline. Follow the syllabus so that you’ll have familiarity with what the instructor is speaking about. Bring your course syllabus, textbook, notebook and any handouts or other important information for each particular class along with a pen and a positive attitude. Become interested in what the instructor has to say. Be eager to learn. Sleep adequately the night before class and ensure you do not arrive to class on an empty stomach. Many courses, both in person and online, use digital platforms called Learning Management Systems (LMS). Examples of these are Canvas, Blackboard, and Moodle. It is important for students to check their e-mail regularly as well as Announcements or notifications from their instructor through the LMS.

Attend Every Class

Attending each and every class requires a lot of self-discipline and motivation. Doing so will help you remain engaged and involved in course topics, provide insight into what your instructor deems most important, allow you to submit work and receive your graded assignments and give you the opportunity to take quizzes or exams that cannot be made up.

Missing class is a major factor in students dropping courses or receiving poor grades. In addition, students attempting to make up the work from missing class often find it overwhelming. It’s challenging to catch up if we get behind.

Take Notes in Class

Hermann Ebbinghaus, a German psychologist, scientifically studied how people forget in the late 1800’s. He is known for his experiments using himself as a subject and tested his memory learning nonsense syllables. One of his famous results, known as the forgetting curve, shows how much information is forgotten quickly after it is learned. Without reviewing, we will forget. Since we forget 42% of the information we take in after only 20 minutes (without review), it is imperative to take notes to remember.

Take Notes When You Are Reading

For the same reason as above, it is helpful to take notes while you are reading to maximize memorization. Sometimes called Active Reading, the goal is to stay focused on the material and to be able to refer back to notes made while reading to improve retention and study efficiency. Don’t make the mistake of expecting to remember everything you are reading. Taking notes when reading requires effort and energy. Be willing to do it and you’ll reap the benefits later.

Know What the Campus Resources Are and Where They Are, and Use Them

There are many campus resources at Harper and it’s likely they are underutilized because students don’t know they exist, where they are or that most of them are free. Find out what is available to you by checking the Harper College website for campus resources and student services or talk to a counselor about what resources may be helpful for you. Check to see where your campus has resources for Counseling, Tutoring, Writing assistance, a Library, Admissions, Records, Financial Aid, Fitness Center, Career Center, Access and Disability Support Services, and other support services.

Read and Retain Your Syllabus

In addition to acting as a contract between the instructor and you, the syllabus is also often the source of information for faculty contact information, textbook information, classroom behavior expectations, attendance policy and course objectives. Some students make the mistake of stuffing the syllabus in their backpack when they receive it on the first day of class and never take a look at it again. Those who clearly read it, keep it for reference and review it frequently find themselves more prepared for class. If there is something in the syllabus you don’t understand, ask your instructor about it before class, after class or during their office hours.

Place Your Assignments on Your Master Calendar and Create Plans for Completing Them Before They Are Due

Place all of your assignments for all of your classes with their due dates in your calendar, planner, smart phone or whatever you use for organization. Successful students will also schedule when to start those assignments and have an idea of how long it will take to complete them.

Complete All of Your Assignments

There will be things that you are more interested in doing than your assignments and unexpected life happenings that will come up. Students who earn good grades have the motivation and discipline to complete all of their assignments.

Have Someone Read Your Papers Before You Submit Them

You might be surprised to learn how many students turn in papers with spelling, grammar and punctuation errors that could have been easily corrected by using a spellchecker program or having someone read your paper. Harper College offer a Writing Center or Tutoring Center, as well as Academic Coaches in specific areas of study, who will read your paper and give feedback, make suggestions, and help shape ideas. Take advantage of these services-they are free! Another strategy is to read your paper aloud to yourself. You may catch errors when you read aloud that you might not catch when reading your writing. Remember that it is always the students’ responsibility to have papers proofread, not someone else’s.

Ask Questions

Many students feel like they are the only one that has a question or the only one that doesn’t understand something in class. Ask questions during class, especially if your instructor encourages them. If not, make the effort to ask your questions before or after class or during your instructors’ office hours.

If you take a class offered online, ask a lot of questions via the preferred method your instructor recommends. Since the delivery method is different to what most students are used to, I believe it is natural for students in online courses to have more questions. Online students may ask questions to understand the material and to be able to successfully navigate through the course content.

Inside information: Instructors expect students to ask questions for both in person and online courses.

Complete All Assigned Reading at The Time It Is Assigned

College courses have much more assigned reading than what most high school students are accustomed to, and it can take a while to become comfortable with the workload. Some students fall behind early in keeping up with the reading requirements and others fail to read it at all. You will be most prepared for your class and for learning if you complete the reading assigned before your class. Staying on top of your syllabus and class calendar will help you be aware of your reading assignment deadlines. There is a difference in assigned reading between high school and college. In high school, if a teacher gave a handout to read in class, students would often read it during class to prepare to participate in a class discussion. In college, more reading is assigned with the expectation it will be done outside of the classroom. It is a big adjustment students need to make in order to be successful.

Study Groups

One of the recent generational differences is that students study less in groups than they used to. Study in the environment that works best for you, but ensure that you try a study group, especially if you are taking a class in a subject in which you are not strong. Study groups can allow for shared resources, new perspectives, answers for questions, faster learning, increased confidence, and increased motivation.

STUDY AREA PRACTICE

- Create a plan for Kai on how to organize a study area in her busy home where she lives with six members of her family. Kai is a first-year college student from Vietnam. She has been in the U.S. with her family for three years and recently passed the English Language Learner classes at the topmost level, so now she looks forward to pursuing her degree in Business Management. She lives with six other family members, her mother, father, grandmother, and three younger siblings aged 14, 12, and 9. Their home is located right next door to the family restaurant. This makes it convenient for Kai and her parents to work their regular shifts and to fill in if one or the other is ill. Kai is also responsible at times to help her younger

Taking Notes in Class

“He listens well who takes notes.”

– Dante Alighieri

Take Notes To Remember

If for no other reason, you should take notes during class so that you do not forget valuable and important information. Despite living with incredible search engines on computers and smart phones that give us a plethora of information 24 hours a day, seven days a week, students do not have the ability to access those during exams. Instructors want to know what you know not what Google knows. We’ve become accustomed to searching for information on demand to find what we need when we need it. The consequence is that we don’t often commit information to memory because we know it will be there tomorrow if we wish to search for it again. This causes challenges with preparation for exams as what we’re tested on is in our brain rather than information we can search for. Thus, there is an importance of taking notes. “Note-taking facilitates both recall of factual material and the synthesis and application of new knowledge, particularly when notes are reviewed prior to exams.”[1]

Hermann Ebbinghaus studied the rate of forgetting and formulated his “forgetting curve” theory. Perform a web search for “Ebbinghaus forgetting curve” to learn more. The curve shows that after one month, only 20 percent of information is retained after initial memorization. Without review, 47 percent of learned information is lost after only 20 minutes. After one day, 62 percent of learned information is lost without review.[2]

In order to try to retain information long term, we must move it from our short-term memory to our long-term memory. One of the best ways to do that is through repetition. The more we review information, and the sooner we review once we initially learn it, the more reinforced that information is in our long-term memory.

The first step in being able to review is to take notes when you are originally learning the information. Students who do not take notes in class in the first place will not be able to recall all of the information covered in order to best review.

Taking notes during lectures is a skill, just like riding a bike. If you have never taken notes while someone else is speaking before, it’s important to know that you will not be an expert at it right away. It is challenging to listen to someone speak and then make a note about what they said, while at the same time continuing to listen to their next thought.

When learning to ride a bike, everyone is going to fall. With practice and concentration, we gain confidence and improve our skill. The more we practice, the better we get. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell refers to the “10,000-hour rule.” Based on research by Anders Ericsson, the rule states that 10,000 hours of dedicated practice in your particular field will allow for the greatest potential of mastery. We do not expect you to practice taking notes for 10,000 hours, but the point is that practice, just like many things, is necessary to become more skilled[3].

Some instructors will give you cues to let you know something is important. If you hear or see one of these cues, it’s something you should write down. This might include an instructor saying, “this is important,” or “this will be covered on the exam.” If you notice an instructor giving multiple examples, repeating information or spending a lot of time with one idea, these may be cues. Writing on the board or presenting a handout or visual information may also be a cue.

There are many different ways to take notes during lectures and we encourage you to find the way that works best for you. Different systems work best for different people. Experiment in different ways to find the most success.

Tips for Taking Notes During the Lecture

Arrive early and find a good seat. Seats in the front and center are best for being able to see and hear information. A seat at the 50-yard line for the Super Bowl is more expensive for a reason: it gives the spectator the greatest experience.

Do not try to write down everything the instructor talks about. It’s impossible and inefficient. Instead, try to distinguish between the most important topics and ideas and write those down. This is also a skill that students can improve upon. You may wish to ask your instructor during office hours if you have identified the main topics in your notes or compare your notes to one of your classmates.

Use shorthand and/or abbreviations. So long as you will be able to decipher what you are writing, the least amount of pen or pencil strokes, the better. It will free you up so you can pay more attention to the lecture and help you be able to determine what is most important.

Write down what your instructor writes. Anything on a dry erase board, chalkboard, overhead projector and in some cases in presentations; these are cues for important information.

Leave space to add information to your notes. You can use this space during or after lectures to elaborate on ideas.

Do not write in complete sentences. Do not worry about spelling or punctuation. Getting the important information, concepts and main ideas is much more important. You can always revise your notes later and correct spelling.

Often, the most important information is delivered at the beginning and/or the end of a lecture. Many students arrive late or pack up their belongings and mentally check out a few minutes before the lecture ends. They are missing out on the opportunity to write down valuable information. Keep taking notes until the lecture is complete.

The Cornell System

One way of taking notes in class is using the Cornell System. Created in the 1950s by Walter Pauk at Cornell University, the Cornell System is still widely used today. Perform a web search for “Cornell note taking method” to find out more.

The note-taking area is for you to use to record notes during lectures.

Students use the column on the left to create questions after the lecture has ended. The questions are based on the material covered. Think of it as a way to quiz yourself. The notes you took should answer the questions you create.

TIPS FOR AFTER THE LECTURE

Consolidate notes as soon as possible after the lecture has ended. Identify the main ideas and underline or highlight them.

Test yourself by looking only at the questions on the left. If you can provide most of the information on the notes side without looking at it, you’re in good shape. If you cannot, keep studying until you improve your retention. Review periodically as needed to keep the information fresh in your mind.

Students use the bottom area for summarizing information. Practice summarizing information — it’s a great study skill. It allows you to determine how information fits together. It should be written in your own words (don’t use the chapter summary in the textbook to write your summary, but check the chapter summary after you write yours for accuracy).

The Outline Method

Another way to take notes is the outline method. Students use an outline to show the relationship between ideas in the lecture. Outlines can help students separate main ideas from supporting details and show how one topic connects to another.

Perform a web search for “outline note taking method” to see what they look like.

Mind Maps

Visual learners may want to experiment with mind maps (also called clustering). Invented by Tony Buzan in the 1960s, it’s another way of organizing information during lectures. Start with a central idea in the center of the paper (landscape is recommended). Using branches (like a tree), supporting ideas can supplement the main idea. Recall everything you can as the lecture is happening. Reorganization can be done later. Perform a web search for mind maps for notetaking.

Review

The most important aspect of reviewing your lecture notes is when your review takes place in relation to when your notes were taken. For maximum efficiency and retention of memory, it’s best to review within 20 minutes of when the lecture ends. For this reason, we do not advise students to take back-to-back classes without 30 minutes in between. It is important to have adequate review time and to give your brain a break. Reviewing shortly after the lecture will allow you to best highlight or underline main points as well as fill in any missing portions of your notes. Students who take lecture notes on a Monday and then review them for the first time a week later often have challenges recalling information that help make the notes coherent.

If you wish to go “above and beyond,” you may consider discussing your notes in a study group with your classmates, which can give you a different perspective on main points and deepen your understanding of the material. You may also want to make flashcards for yourself with vocabulary terms, formulas, important dates, people, places, etc.

The Big Picture

Keep in mind that students who know what their instructor is going to lecture on before the lecture are at an advantage. Why? Because the more they understand about what the instructor will be talking about, the easier it is to take notes. How? Take a look at the syllabus before the lecture. It won’t take much time but it can make a world of difference. You will also be more prepared and be able to see important connections if you read your assigned reading before the lecture. It’s not easy to do, but students that do it will be rewarded. Online flash cards are another option. Students can make them for free and test themselves online or on their phone.

Reading to Understand

Most students entering college have not yet dealt with the level of difficulty involved in reading–and comprehending–scholarly textbooks and articles. The challenge may even surprise some who have pretty good reading and comprehension skills so far. Other students for whom reading has mostly consisted of social media, texts, forum chat rooms, and emails, find they are intimidated by the sheer amount of reading there is in college classes.

Reading Comprehension Definition

Reading comprehension is defined as the level of understanding of a message. This understanding comes from the interaction between the words that are written and how they trigger knowledge outside the text/message. Comprehension is a “creative, multifaceted process” dependent upon four language skills: phonology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Proficient reading depends on the ability to recognize words quickly and effortlessly. It is also determined by an individual’s cognitive development, which is “the construction of thought processes.” Some people learn through education or instruction and others through direct experiences.

There are specific traits that determine how successfully an individual will comprehend text, including prior knowledge about the subject, well-developed language, and the ability to make inferences. Having the skill to monitor comprehension is a factor: “Why is this important?” and “Do I need to read the entire text?” are examples. Another trait is the ability to be self-correcting, which allows for solutions to comprehension challenges.

Reading Comprehension Levels

Reading comprehension involves two levels of processing, shallow (low-level) processing and deep (high-level) processing. Deep processing involves semantic processing, which happens when we encode the meaning of a word and relate it to similar words. Shallow processing involves structural and phonemic recognition, the processing of sentence and word structure and their associated sounds. This theory was first identified by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart.

Brain Region Activation

Comprehension levels can now be observed through the use of a fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging. fMRIs’ are used to determine the specific neural pathways of activation across two conditions, narrative-level comprehension and sentence-level comprehension. Images showed that there was less brain region activation during sentence-level comprehension, suggesting a shared reliance with comprehension pathways. The scans also showed an enhanced temporal activation during narrative levels tests indicating this approach activates situation and spatial processing.

History

Initially most comprehension teaching was based on imparting selected techniques that when taken together would allow students to be strategic readers. However, in 40 years of testing these methods never seemed to win support in empirical research. One such strategy for improving reading comprehension is the technique called SQ3R: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review, that was introduced by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1946 book Effective Study.[4]

Between 1969 and to about 2000 a number of “strategies” were devised for teaching students to employ self-guided methods for improving reading comprehension. In 1969 Anthony Manzo designed and found empirical support for the ReQuest, or Reciprocal Questioning Procedure, it was the first method to convert emerging theories of social and imitation learning into teaching methods through the use of a talk rotation between students and teacher called cognitive modeling.[5]

Since the turn of the 21st century, comprehension lessons usually consist of students answering teachers’ questions, writing responses to questions on their own, or both. The whole group version of this practice also often included “Round-robin reading”, wherein teachers called on individual students to read a portion of the text. In the last quarter of the 20th century, evidence accumulated that the read-test methods were more successful assessing rather than teaching comprehension. Instead of using the prior read-test method, research studies have concluded that there are much more effective ways to teach comprehension. Much work has been done in the area of teaching novice readers a bank of “reading strategies,” or tools to interpret and analyze text.

Instruction in comprehension strategy use often involves the gradual release of responsibility, wherein teachers initially explain and model strategies. Over time, they give students more and more responsibility for using the strategies until they can use them independently. This technique is generally associated with the idea of self-regulation and reflects social cognitive theory, originally conceptualized by Albert Bandura.[6]

Vocabulary

Reading comprehension and vocabulary are inextricably linked. The ability to decode or identify and pronounce words is self-evidently important, but knowing what the words mean has a major and direct effect on knowing what any specific passage means. Students with a smaller vocabulary than other students comprehend less of what they read and it has been suggested that the most impactful way to improve comprehension is to improve vocabulary.

Most words are learned gradually through a wide variety of environments: television, books, and conversations. Some words are more complex and difficult to learn, such as homonyms, words that have multiple meanings and those with figurative meanings, like idioms, similes, and metaphors.

Three Tier Vocabulary Words

Several theories of vocabulary instruction exist, namely, one focused on intensive instruction of a few high value words, one focused on broad instruction of many useful words, and a third focused on strategies for learning low frequency, context specific vocabulary.

Broad Vocabulary Approach

The method of focusing of broad instruction on many words was developed by Andrew Biemiller who argued that more words would benefit students more, even if the instruction was short and teacher-directed. He suggested that teachers teach a large number of words before reading a book to students, by merely giving short definitions, such as synonyms, and then pointing out the words and their meaning while reading the book to students. The method contrasts with the approach by emphasizing quantity versus quality. There is no evidence to suggest the primacy of either approach.

Morphemic Instruction

Another vocabulary technique, strategies for learning new words, can be further subdivided into instruction on using context and instruction on using morphemes, or meaningful units within words to learn their meaning. Morphemic instruction has been shown to produce positive outcomes for students reading and vocabulary knowledge, but context has proved unreliable as a strategy and it is no longer considered a useful strategy to teach students. This conclusion does not disqualify the value in “learning” morphemic analysis – prefixes, suffixes and roots – but rather suggests that it be imparted incidentally and in context. Accordingly, there are methods designed to achieve this, such as Incidental Morpheme Analysis.

Reciprocal Teaching

In the 1980s Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar and Ann L. Brown developed a technique called reciprocal teaching that taught students to predict, summarize, clarify, and ask questions for sections of a text. The use of strategies like summarizing after each paragraph have come to be seen as effective strategies for building students’ comprehension. The idea is that students will develop stronger reading comprehension skills on their own if the teacher gives them explicit mental tools for unpacking text.

Instructional Conversations

“Instructional conversations”, or comprehension through discussion, create higher-level thinking opportunities for students by promoting critical and aesthetic thinking about the text. There are several types of questions that a teacher should focus on: remembering; testing understanding; application or solving; invite synthesis or creating; and evaluation and judging. Teachers should model these types of questions through “think-alouds” before, during, and after reading a text. When a student can relate a passage to an experience, another book, or other facts about the world, they are “making a connection.” Making connections helps students understand the author’s purpose and fiction or non-fiction story.

Text Factors

There are factors, that once discerned, make it easier for the reader to understand the written text. One is the genre, like folktales, historical fiction, biographies or poetry. Each genre has its own characteristics for text structure, that once understood help the reader comprehend it. A story is composed of a plot, characters, setting, point of view, and theme. Informational books provide real world knowledge for students and have unique features such as: headings, maps, vocabulary, and an index. Poems are written in different forms and the most commonly used are: rhymed verse, haiku, free verse, and narratives. Poetry uses devices such as: alliteration, repetition, rhyme, metaphors, and similes. “When children are familiar with genres, organizational patterns, and text features in books they’re reading, they’re better able to create those text factors in their own writing.”

The Reading Apprenticeship (RA) Approach to Comprehension

This next section focuses on a method called Reading Apprenticeship. It is based on the premise that people who have become expert readers can assist learners by modeling what they have learned to do. As explained in the text, Reading for Understanding, How Reading Apprenticeship Improves Disciplinary Learning in Secondary and College Classrooms, “One literacy educator describes the idea of the cognitive apprenticeship in reading by comparing the process of learning to read with that of learning to ride a bike. In both cases, a more proficient other is present to support the beginner, engaging the beginner in the activity and calling attention to often overlooked or hidden strategies.”[7]

This is a strategy that takes a metacognitive approach to comprehension, utilizing various strategies readers may already know they know how to do, then adding more. For example, most readers have learned to make predictions, ask questions concerning meanings (“I wonder about…”), visualize a scene being described, associate the material being read to some other material, and, at the end, summarize the material.

Now review and affirm important comprehension skills you already possess and complete the exercise below.

COMPREHENSION SKILLS PRACTICE

Go back through the excerpt, above, on reading comprehension and THIS time, write marginal notes where you used any of the comprehension tools listed below:

- predicting

- asking questions of the material such as, “I wonder about,” “Could this mean?”

- visualizing

- connecting this material to something else you have learned

- noting where you think you might need to read something over again for comprehension

- summarizing

Master Reading

“There is more treasure in books than in all the pirate’s loot on Treasure Island.”

– Walt Disney

Practice

If you want to be a better swimmer, you practice. If you want to be a better magician, you practice. If you want to be a better reader, you practice. Read, read, read. Read newspapers. Read magazines. Read books. Use your library card (get one if you don’t have one). Read blogs. Read tweets. Read Wikipedia articles. Read about history, politics, world leaders, current events, sports, art, music—whatever interests you. Why? Because the more you read, the better reader you become. And because the more you read, the more knowledge you will have. That is an important piece in learning and understanding. When we are learning new information, it’s easier to learn if we have some kind of background knowledge about it.

Background Knowledge

In their book, Content Area Reading: Literacy and Learning Across the Curriculum, the authors postulate that a student’s prior knowledge is “the single most important resource in learning with texts.”[8]

Reading and learning are processes that work together. Students draw on prior knowledge and experiences to make sense of new information. “Research shows that if learners have advanced knowledge of how the information they’re about to learn is organized — if they see how the parts relate to the whole before they attempt to start learning the specifics — they’re better able to comprehend and retain the material.”[9]

For example, you are studying astronomy and the lecture is about Mars. Students with knowledge of what Mars looks like, or how it compares in size to other planets or any information about Mars will help students digest new information and connect it to prior knowledge. The more you read, the more background knowledge you have, and the better you will be able to connect information and learn. “Content overlap between text and knowledge appears to be a necessary condition for learning from text.”[10]

There are a lot of recent advances in technology that have made information more accessible to us. Use this resource! If you are going to read a chemistry textbook, experiment with listening or watching a podcast or a YouTube video on the subject you are studying. Ask your instructor if they recommend specific websites for further understanding.

“The greatest gift is a passion for reading. It is cheap, it consoles, it distracts, it excites, it gives you the knowledge of the world and experience of a wide kind. It is a moral illumination.”

– Elizabeth Hardwick

The Seven Reading Principles

Read the assigned material. You might be surprised to learn how many students don’t read the assigned material. Often, it takes longer to read the material than had been anticipated. Sometimes it is not interesting material to us and we procrastinate reading it. Sometimes we’re busy and it is just not a priority. It makes it difficult to learn the information your instructor wants you to learn if you do not read about it before coming to class.

Read it when assigned. This is almost as big of a problem for students as the first principle. You will benefit exponentially from reading assignments when they are assigned (which usually means reading them before the instructor lectures on them). If there is a date for a reading on your syllabus, finish reading it before that date. The background knowledge you will attain from reading the information will help you learn and connect information when your instructor lectures on it, and it will leave you better prepared for class discussions. Further, if your instructor assigns you 70 pages to read by next week, don’t wait until the night before to read it all. Break it down into chunks. Try scheduling time each day to read 10 or so pages. It takes discipline and self-control but doing it this way will make understanding and remembering what you read much easier.

Take notes when you read. Hermann Ebbinghaus did research suggesting that a huge portion of the information we take in is lost after only 20 minutes without review. For the same reasons that it’s important to take notes during lectures, it’s important to take notes when you are reading. Your notes will help you concentrate, remember and review. Ebbinghaus also found that repetition combats much of the forgetting that happens, meaning reviewing your notes often will help you retain more information.[11]

Relate the information to you. We remember information that we deem is important. The strategy then is to make what you are studying important to you. Find a way to directly relate what you are studying to something in your life. Sometimes it is easy and sometimes it is not. But if your attitude is “I will never use this information” and “it’s not important,” chances are good that you will not remember it.

Read with a dictionary or use an online dictionary. Especially with information that is new to us, we may not always recognize all the words in a textbook or their meanings. If you read without a dictionary and you don’t know what a word means, you probably still won’t know what it means when you finish reading. Students who read with a dictionary (or who look the word up online) expand their vocabulary and have a better understanding of the text. Take the time to look up words you do not know. Another strategy is to try to determine definitions of unknown words by context, thus eliminating the interruption to look up words.

Ask a classmate or instructor when you have questions or if there are concepts you do not understand. Visiting an instructor’s office hours is one of the most underutilized college resources. Oftentimes, students are shy about going, and while this is understandable, ultimately, it’s your experience, and it’s up to you if you want to make the most of it. If you go, you will get answers to your questions; at the same time, you’ll demonstrate to your instructor that their course is important to you. Find out when your professor’s office hours are (they are often listed in the syllabus), ask before or after class or e-mail your professor to find out. Be polite and respectful.

Read it again. Some students will benefit from reading the material a second or third time as it allows them to better understand the material. The students who understand the material the best usually score the highest on exams. It may be especially helpful to reread the chapter just after the instructor has lectured on it.

Strategies To Think About When You Open Your Textbook

Preview: Look at what you are reading and how it is connected with other areas of the class. How does it connect with the lecture? How does it connect with the course description? How does it connect with the syllabus or with a specific assignment? What piece of the puzzle are you looking at and how does it fit into the whole picture? If your textbook has a chapter summary, reading it first may help you preview and understand what you are going to be reading.

Headings and designated words: Pay close attention to section headings and subheadings, and boldface, underlined or italicized words and sentences. There is a reason why these are different than regular text. The author feels they are more important and so should you.

Highlighting: Highlighting is not recommended because there is not evidence supporting it helps students with reading comprehension or higher test scores.[12] Highlighting, alone, is not as beneficial, as highlighting along with notetaking.

Pace: One of the biggest challenges with reading is accurately assessing how long it will take to read what is assigned. In many cases, it’s important to break the information up in chunks rather than to try and read it all at once. If you procrastinate and leave it until the day before it needs to be read, and then find out it will take you longer than you anticipate, it causes problems. One strategy that works well for many students is to break the information up equally per day and adjust accordingly if it takes longer than you had thought. Accurately estimating how much time it will take to practice the seven reading principles applied to your reading assignments is a skill that takes practice.

“Drink Deeply from Good Books”

– John Wooden

It’s Not All Equal

Keep in mind that the best students develop reading skills that are different for different subjects. The main question you want to ask yourself is: Who are you reading for? And what are the questions that drive the discipline? We read different things for different purposes. Reading texts, blogs, leisure books and textbooks are all different experiences, and we read them with different mindsets and different strategies. The same is true for textbooks in different areas. Reading a mathematics textbook is going to be different than reading a history textbook, a psychology textbook, a Spanish textbook or a criminal justice textbook. Further, students may be assigned to read scientific journals or academic articles often housed in college libraries’ online databases. Scholarly articles require a different kind of reading and librarians are a resource for how to find and read this kind of information. Applying the principles in this chapter will help with your reading comprehension, but it’s important to remember that you will need to develop specific reading skills most helpful to the particular subject you are studying.

Memory

“The more often you share what you’ve learned, the stronger that information will become in your memory.”

-Steve Brunkhorst

An Information Processing Model

Once information has been encoded, we have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

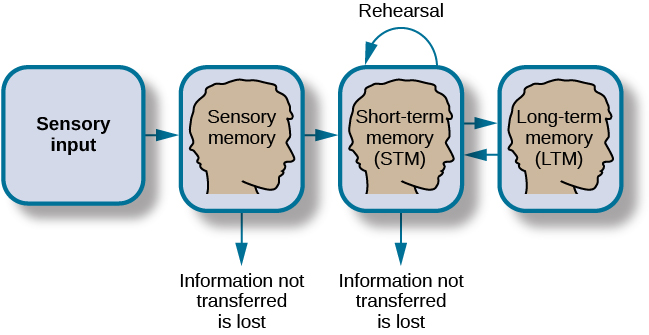

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

Learning, Remembering, and Retrieving Information Is Important for Academic Success

The first thing our brains do is to take in information from our senses (what we see, hear, taste, touch and smell). In many classroom and homework settings, we primarily use hearing for lectures and seeing for reading textbooks. Information we perceive from our senses is stored in what we call the short-term memory.

It is useful to then be able to do multiple things with information in the short-term memory. We want to: 1) decide if that information is important; 2) for the information that is important, be able to save the information in our brain on a longer-term basis—this storage is called the long-term memory; 3) retrieve that information when we need to. Exams often measure how effectively the student can retrieve “important information.”

In some classes and with some textbooks it is easy to determine information important to memorize. In other courses with other textbooks, that process may be more difficult. Your instructor can be a valuable resource to assist with determining the information that needs to be memorized. Once the important information is identified, it is helpful to organize it in a way that will help you best understand.

Moving Information from the Short-term Memory To the Long-term Memory

This is something that takes a lot of time: there is no shortcut for it. Students who skip putting in the time and work often end up cramming at the end.

Preview the information you are trying to memorize. The more familiar you are with what you are learning, the better. Create acronyms like SCUBA for memorizing “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus.” Organizing information in this way can be helpful because it is not as difficult to memorize the acronym, and with practice and repetition, the acronym can trigger the brain to recall the entire piece of information.

Flash cards are a valuable tool for memorization because they allow students to be able to test themselves. They are convenient to bring with you anywhere, and can be used effectively whether a student has one minute or an hour.

Once information is memorized, regardless of when the exam is, the last step is to apply the information. Ask yourself: In what real-world scenarios could you apply this information? And for mastery, try to teach the information to someone else.

Concentration and Distraction

“Starve your distractions, feed your focus.”

-Daniel Goleman

Where To Study

In order to study successfully, students must learn to concentrate at a high level. It is important to know where we study best. Some students study well at home. Other students study well at a library or coffee shop. There is no best for all. Your best environment is based on you and your preferences.

Watch this selective attention test video and see if you come up with the correct answer.

Video: Selective Attention

When To Study

It is also important to know when we study best. Many students are most efficient studying in the morning when they are fresh. Studying late in the day may be the only option for some students but often we are tired at the end of the day, and this can have a major effect on study efficiency. Figuring out where and when we study best may take some time. And even when we find the best place and time to study, we also have to be aware of distractions, which can be internal or external.

Internal Distractions

An internal distraction includes thought processes, self-esteem, or confidence. It’s something that interrupts you from what you’re doing. It might also be a computer or cell phone – something that is controlled by you. Many students intend to study but easily get distracted with surfing the Internet, checking social media, watching YouTube videos, or receiving a text message. If you don’t absolutely need your computer or cell phone for your study, try to not bring them or turn them off. If you do study with your phone or computer, it is best to have all potential alerts turned off. Notifications of text messages, emails, or social media updates all can serve as a major distraction to your studying.

External Distractions

External distractions might be your peers, family or friends. Even if they are supportive of your study, it may be challenging to concentrate when they are around. Saying “no” is an important skill that may need to be utilized in order for you to have your study time without interruption.

Keep in mind that it may take 20 minutes to reach a high level of concentration. When we are interrupted, it takes on average another 23 minutes to get back to the level of concentration that we were at prior to the disruption.[13] If a student is studying for an hour and is interrupted twice, the consequence to study efficiency is devastating.

One way to try to monitor how many interruptions you incur and how well you maintain your level of concentration is to keep track of it. Take a blank piece of paper when you are studying and mark down each time you were interrupted.

Over time, with practice, you should be able to decrease the number of interruptions you incur. This will allow you to be most efficient when studying.

It is it odd to think that before cell phones, we invented the answering machine. Its purpose was to allow us to receive a message when someone called if we were not home or it was not convenient to answer the phone at the time. In contrast, text messaging is designed in most cases (user’s notification preferences) to interrupt us and alert us immediately that someone has contacted us. Whatever your opinion may be on this, the point is to tread cautiously when using technology that may be addicting and may frequently (consciously or unconsciously) distract you from studying and concentrating.

Multitasking

Millennials are considered extraordinary multitaskers, though brain science tells us that multitasking is a myth.[14] More likely, they are apt to switch tasks quickly enough to appear to be doing them simultaneously. When it comes to heavy media multitasking, studies show greater vulnerability to interference, leading to decreased performance.[15]

FYS classes can have lively discussions on multitasking. Most of the time, First Year Seminar instructors are trying to convince students that multitasking is not a good idea for them. (There are always a few stubborn hold outs). Trying to do multiple things at the same time may seem like it may allow you to accomplish more but when studying it often leads to accomplishing less. There are things that can be successfully multitasked. For example, throwing clothes in the washer and making a snack, then eating and reading a book at the same time while waiting for the clothes to be washed, lends itself to multitasking. But trying to text, check e-mail, watch TV and look at Twitter, all while studying, won’t work well.

A study from Carnegie Mellon University found that driving while listening to a cell phone reduces the amount of brain activity associated with driving by 37 percent.[16] Why would anyone choose to use less brain activity when they study?

Breaking Down Tests

Pre-Test Strategies

Q: When should you start preparing for the first test? Circle…

- The night before.

- The week prior.

- The first day of classes.

If you answered “3. The first day of classes,” you are correct. If you circled all three, you are also correct. Preparing to pass tests is something that begins when learning begins and continues all the way through to the final exam.

Many students, however, don’t start thinking about test taking, whether weekly exams, mid-terms, or finals, until the day before when they engage in an all-nighter, or cramming. Additionally, unless memory devices are used to aid memory and to cement information into long term memory (or at least until the test is over tomorrow!) chances are slim that students who cram will effectively learn and remember the information.

Additionally, a lot of students are unaware of the many strategies available to help with the test-taking experience before, during, and after. For starters, take a look at what has helped you so far.

PRE-TEST TAKING STRATEGIES PRACTICE

PART A:

Put a check mark next to the pre-test strategies you already employ.

____ Organize your notebook and other class materials the first week of classes.

____ Maintain your organized materials throughout the term.

____ Take notes on key points from lectures and other materials.

____ Make sure you understand the information as you go along.

____ Access your instructor’s help and the help of a study group, as needed.

____ Organize a study group, if desired.

____ Create study tools such as flashcards, graphic organizers, etc. as study aids.

____ Complete all homework assignments on time.

____ Review likely test items several times beforehand.

____ Ask your instructor what items are likely to be covered on the test.

____ Ask your instructor if she or he can provide a study guide or practice test.

____ Ask your instructor if he/she gives partial credit for test items such as essays.

____ Maintain an active learner attitude.

____ Schedule extra study time in the days just prior to the test.

____ Gather all notes, handouts, and other materials needed before studying.

____ Review all notes, handouts, and other materials.

____ Organize your study area for maximum concentration and efficiency.

____ Create and use mnemonic devices to aid memory.

____ Put key terms, formulas, etc., on a single study sheet that can be quickly reviewed.

____ Schedule study times short enough (1-2 hours) so you do not get burned out.

____ Get plenty of sleep the night before.

____ Set a back-up alarm in case the first alarm doesn’t sound or you sleep through it.

____ Have a good breakfast with complex carbs and protein to see you through.

____ Show up 5-10 minutes early to get completely settled before the test begins.

____ Use the restroom beforehand to minimize distractions.

PART B

By reviewing the pre-test strategies, above, you have likely discovered new ideas to add to what you already use. Make a list of them.

Mid-Test Strategies

Here is a list of the most common–and useful–strategies to survive this ubiquitous college experience.

- Scan the test, first, to get the big picture of how many test items there are, what types there are (multiple choice, matching, essay, etc.), and the point values of each item or group of items.

- Determine which way you want to approach the test: Some students start with the easy questions first, that is, the ones they immediately know the answers to, saving the difficult ones for later, knowing they can spend the remaining time on them. Some students begin with the biggest-point items first, to make sure they get the most points.

- Determine a schedule that takes into consideration how long you have to test, and the types of questions on the test. Essay questions, for example, will require more time than multiple choice, or matching questions.

- Keep your eye on the clock.

- If you can mark on the test, put a check mark next to items you are not sure of just yet. It is easy to go back and find them to answer later on. You might just find help in other test questions covering similar information.

- Sit where you are most comfortable. That said, sitting near the front has a couple of advantages: You may be less distracted by other students. If a classmate comes up with a question for the instructor and there is an important clarification given, you will be better able to hear it and apply it, if needed.

- Wear ear plugs, if noise distracts you.

- You do NOT have to start with #1! It you are unsure of it, mark it to come back to later on.

- Bring water…this helps calm the nerves, for one, and water is also needed for optimum brain function.

- If permitted, get up and stretch (or stretch in your chair) from time to time to relieve tension and assist the blood to the brain!

- Remember to employ strategies to reduce test-taking anxiety (covered in the next lesson)

If despite all of your best efforts to prepare for a test you just cannot remember the answer to a given item for multiple choice, matching, and/or true/false questions, employ one or more of the following educated guessing (also known as “educated selection”) techniques. By using these techniques, you have a better chance of selecting the correct answer. It is usually best to avoid selecting an extreme or all-inclusive answer (also known as 100% modifiers) such as “always,” and “never”. Choose, instead, words such as “usually,” “sometimes,” etc. (also known as in-between modifiers). If the answers are numbers, choose one of the middle numbers. If you have options such as “all of the above,” or “both A and B,” make sure each item is true before selecting those options. Choose the longest, or most inclusive, answer. Make sure to match the grammar of question and answer. For example, if the question indicates a plural answer, look for the plural answer. Regarding matching tests: count both sides to be matched. If there are more questions than answers, ask if you can use an answer more than once. Pay close attention to items that ask you to choose the “best” answer. This means one answer is better or more inclusive than a similar answer. Read all of the response options.

Post-Test Strategies

In addition to sighing that big sigh of relief, here are a few suggestions to help with future tests.

- If you don’t understand why you did not get an item right, ask the instructor. This is especially useful for quizzes that contain information that may be incorporated into more inclusive exams such as mid-terms and finals.

- Analyze your results to help you in the future. For example, see if most of your incorrect answers were small things such as failing to include the last step in a math item, or neglecting to double-check for simple errors in a short-answer or essay item. See where in the test you made the most errors: beginning, middle, or end. Also analyze which type of questions, true/false, multiple choice, essay, etc. And which topics were missed. This will help you pay closer attention to those sections in the future.

TEST TAKING TIPS PRACTICE

Write a letter of advice to Teo incorporating 10 test-taking tips and strategies you think will help him.

Teo believes he is good at organization, and he usually is–for about the first two weeks of classes. He then becomes overwhelmed with all of the handouts and materials and tends to start slipping in the organization department. When it comes to tests, he worries that his notes might not cover all of the right topics and that he will not be able to remember all of the key terms and points–especially for his math class. During tests, he sometimes gets stuck on an item and tends to spend too much time there. He also sometimes changes answers but finds out later that his original selection was correct. Teo is also easily distracted by other students and noises which makes it hard for him to concentrate sometimes, and, unfortunately, he does admit to occasionally “cramming” the night before.

Test Taking Strategies

“By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

– Benjamin Franklin

Discipline, Preparation and Execution

Test taking (with few exceptions) comes down to discipline, preparation and execution. Students wanting to be successful have to have the self-discipline to schedule time to study well in advance of the exam. They have to actually do the work: the preparation needed in order to have the best opportunity for success on the exam. Then they must execute: they have to be able to apply their preparation accordingly and perform well on the exam.

Preparation for an exam is not glamorous. It’s easy to find other things to do that are more interesting and fun. Students need to keep themselves motivated with their “eyes on the prize.” Think of it like this: if the most important event of your life was coming up and you wanted to perform to the best of your ability in that event, you would likely spend some time preparing for it, rehearsing for it, practicing it, etc. A student may argue that an exam they will be taking would not be the most important event of their life. If you’re already spending the time, effort, energy and money to attend college, why not do it to the best of your ability?

It would be beneficial to spread this preparation and practice out over time and prepare periodically rather than to wait until the last minute and binge study or cram. Your preparation would not be the same and this may affect your test score. Binge studying and cramming also are not healthy. Staying up late puts stress on our brain and body, and not getting adequate sleep places our bodies at risk for getting sick.

“One of the most important keys to success is having the discipline to do what you know you should do, even when you don’t feel like doing it.”

– Unknown

“The will to succeed is important, but what’s more important is the will to prepare.”

– Bobby Knight

Everyone wants to be successful. When the exam is passed out, everyone wants to perform well. What often separates successful students and less successful students is the preparation time put into the studying process.

Studying the right thing is a process and a skill. As you gain more experience, you will learn how to become better at knowing what to study. It can be very frustrating to spend a lot of time preparing and studying and then finding out that what you studied was not on the exam. You will see a lot of variance with exams due to different instructors, classes and types of tests. The better you become at predicting what will be on the exam and study accordingly, the better you will perform on your exams. Try placing yourself in your instructor’s shoes and design questions you think your instructor would ask. It’s often an eye-opening experience for students and a great study strategy.

Preparation for Exam Strategies

FIND OUT AS MUCH ABOUT THE EXAM IN ADVANCE AS YOU CAN

Some professors will tell you how many questions there will be, what format the exam will be in, how much time you will have, etc., and others will not. Students should ask questions about the exam if there is not information given. Ask those questions before class, after class, in professors’ office hours or via e-mail rather than during class.

KNOW THE TEST

If you know how many questions, what the format is, and/or how much time you will have, you can start to mentally prepare for the exam much more so than if you are coming in with no information. There are two more important aspects that you may or may not know: a) what will be covered or asked on the exam; b) how the exam will be scored. Obviously, the more you know about what will be covered, the easier it is for you to be able to prepare for the exam. Most exam scoring is standardized, but not always.

Look for opportunities where some areas of the exam are worth more points than others. For example: An exam consists of 21 questions, with 10 being True/False, 10 being multiple choice, and one essay question. The T/F questions are worth 1 point each (10 points), the multiple-choice questions are worth 2 points each (20 points), and the essay question is worth 30 points. We know that the essay question is the most valuable (it is worth half of the value of the exam). And we should allocate our time for it accordingly. Start with the essay question. Do a quick analysis of time to be able to spend your time on the exam wisely. You want to spend some time with the exam question since it is so valuable, without sacrificing adequate time to ensure the T/F and multiple-choice questions are answered.

Often, the order of the exam in this scenario will be: T/F first, multiple choice second and essay third. Most students will go in the chronological order of the exam, but a savvy student would start with the essay. If an exam were to last for 30 minutes with this format of questions, spend 15 minutes on the essay question, ten minutes on the multiple choice, three minutes on the T/F and two minutes reviewing their answer.

Also, look for situations where exams penalize students for incorrectly answering a question. This does not occur very often, but is the case with some exams. The strategy for a multiple-choice question is: if you can narrow down the potentially correct answer to two rather than four or five, it is statistically advantageous to answer the question and guess between the two answers; however, if a student had no idea if any of the answers were correct or incorrect, it would be best to leave the answer blank. Remember, this is rare, but it is important to understand the strategy when students take these exams.

In conclusion, the more information you have about the exam, the better you can prepare for content, allocation of time spent on aspects of the exam, and the more confident you will be in knowing how and when to attempt to answer questions.

Strategies for Specific Exam Formats

TRUE OR FALSE QUESTIONS

Look for qualifiers. A qualifier is a word that is absolute. Examples are: all, never, no, always, none, every, only, entirely. They are often seen in false statements. This is because it is more difficult to create a true statement using a qualifier like never, no, always, etc. For example, “All cats chase mice.” Cats may be known for chasing mice, but not all of them do so. The answer here is false and the qualifier “all” gave us a tip. Qualifiers such as: sometimes, many, some, most, often, and usually are commonly found in true statements. For example: “Most cats chase mice.” This is true and the qualifier “most” gave us a tip.

Make sure to read the entire statement. All parts of a sentence must be true if the whole statement is to be true. If one part of it is false, the whole sentence is false. Long sentences are often false for this reason.

Students should make an educated guess on True or False questions they do not know the answer to unless there is a penalty for an incorrect answer.

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS

Think of multiple choice questions as four (or five) true or false statements in one. One of the statements is true (the correct answer) and the others will be false. Apply the same strategy toward qualifiers. If you see an absolute qualifier in one of the answer choices, it is probably false and not the correct answer. Try to identify the true statement. If you can do this, you have the answer as there is only one. If you cannot do this at first, try eliminating answers you know to be false.

If there is no penalty for incorrect answers, guess if you are not certain of the answer. If there is a penalty for incorrect answers, common logic is to guess if you can eliminate two of the answers as incorrect (pending what the penalty is). If there’s a penalty and you cannot narrow down the answers, it’s best to leave it blank. You may wish to ask your instructor for clarification.

Answers that are strange and unrelated to the question are usually false. If two answers have a word that looks or sounds similar, one of those is usually correct. For example: abductor/ adductor. If you see these as two of the four or five choices, one of them is usually correct. Also look for answers that are grammatically incorrect. These are usually incorrect answers. If you have to completely guess, choose B or C. It is statistically proven to be correct more than 25 percent of the time. If there are four answers for each question, and an exam had standardized the answers, each answer on the exam A, B, C and D would be equal. But most instructors do not standardize their answers, and more correct answers are found in the middle (B and C then the extremes A and D or E). “People writing isolated four-choice questions hide the correct answer in the two middle positions about 70% of the time.”[17] This is 20 percent more correct answers found in B or C than a standardized exam with equal correct answers for each letter.

MATCHING QUESTIONS

Although less common than the other types of exams, you will likely see some matching exams during your time in college. First, read the instructions and take a look at both lists to determine what the items are and their relationship. It is especially important to determine if both lists have the same number of items and if all items are to be used, and used only once.

Matching exams become much more difficult if one list has more items than the other or if items either might not be used or could be used more than once. If your exam instructions do not discern this, you may wish to ask your instructor for further clarification. I advise students to take a look at the whole list before selecting an answer because a more correct answer may be found further into the list. Mark items when you are sure you have a match (pending the number of items in the list this may eliminate answers for the future). Guessing (if needed) should take place once you have selected answers you are certain about.

SHORT-ANSWER QUESTIONS

Read all of the instructions first. Budget your time and then read all of the questions. Answer the ones you know best or feel the most confident with. Then go back to the other ones. If you do not know the answer and there is no penalty for incorrect answers, guess. Use common sense. Sometimes instructors will award partial credit for a logical answer that is related even if it is not the correct answer.

ESSAY QUESTIONS