13 Sustainability

Matthew R. Fisher

Environment & Sustainability

The Evolution of Sustainability Itself

Our Common Future (1987), the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, is widely credited with having popularized the concept of sustainable development. It defines sustainable development in the following ways…

- …development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- … sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the orientation of the technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs.

The concept of sustainability, however, can be traced back much farther to the oral histories of indigenous cultures. For example, the principle of inter-generational equity is captured in the Inuit saying, ‘we do not inherit the Earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children’. The Native American ‘Law of the Seventh Generation’ is another illustration. According to this, before any major action was to be undertaken its potential consequences on the seventh generation had to be considered. For a species that at present is only 6,000 generations old and whose current political decision-makers operate on time scales of months or few years at most, the thought that other human cultures have based their decision-making systems on time scales of many decades seems wise but unfortunately inconceivable in the current political climate.

17 Goals to Transform Our World

The Sustainable Development Goals are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere. The 17 Goals were adopted by all UN Member States in 2015, as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which set out a 15-year plan to achieve the Goals.

- Sustainable development has been defined as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- Sustainable development calls for concerted efforts towards building an inclusive, sustainable and resilient future for people and planet.

- For sustainable development to be achieved, it is crucial to harmonize three core elements: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. These elements are interconnected and all are crucial for the well-being of individuals and societies.

- Eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions is an indispensable requirement for sustainable development. To this end, there must be promotion of sustainable, inclusive and equitable economic growth, creating greater opportunities for all, reducing inequalities, raising basic standards of living, fostering equitable social development and inclusion, and promoting integrated and sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems.

Today, progress is being made in many places, but, overall, action to meet the Goals is not yet advancing at the speed or scale required. 2020 needs to usher in a decade of ambitious action to deliver the Goals by 2030.

With just under ten years left to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, world leaders at the SDG Summit in September 2019 called for a Decade of Action and delivery for sustainable development, and pledged to mobilize financing, enhance national implementation and strengthen institutions to achieve the Goals by the target date of 2030, leaving no one behind.

The UN Secretary-General called on all sectors of society to mobilize for a decade of action on three levels: global action to secure greater leadership, more resources and smarter solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals; local action embedding the needed transitions in the policies, budgets, institutions and regulatory frameworks of governments, cities and local authorities; and people action, including by youth, civil society, the media, the private sector, unions, academia and other stakeholders, to generate an unstoppable movement pushing for the required transformations.

Environmental Equity

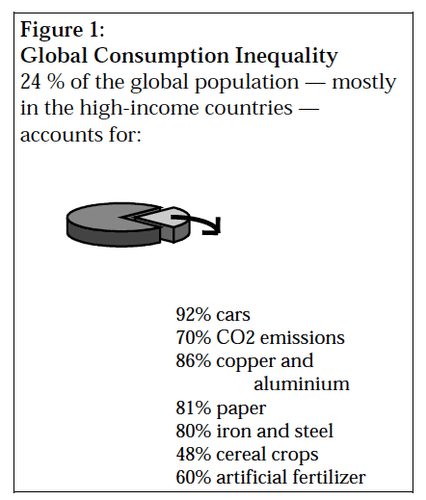

While much progress is being made to improve resource efficiency, far less progress has been made to improve resource distribution. Currently, just one-fifth of the global population is consuming three-quarters of the earth’s resources (Figure 1). If the remaining four-fifths were to exercise their right to grow to the level of the rich minority it would result in ecological devastation. So far, global income inequalities and lack of purchasing power have prevented poorer countries from reaching the standard of living (and also resource consumption/waste emission) of the industrialized countries.

Countries such as China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia are, however, catching up fast. In such a situation, global consumption of resources and energy needs to be drastically reduced to a point where it can be repeated by future generations. But who will do the reducing? Poorer nations want to produce and consume more. Yet so do richer countries: their economies demand ever greater consumption-based expansion. Such stalemates have prevented any meaningful progress towards equitable and sustainable resource distribution at the international level. These issue of fairness and distributional justice remain unresolved.

Sustainable Ethic

A sustainable ethic is an environmental ethic by which people treat the earth as if its resources are limited. This ethic assumes that the earth’s resources are not unlimited and that humans must use and conserve resources in a manner that allows their continued use in the future. A sustainable ethic also assumes that humans are a part of the natural environment and that we suffer when the health of a natural ecosystem is impaired. A sustainable ethic includes the following tenets:

- The earth has a limited supply of resources.

- Humans must conserve resources.

- Humans share the earth’s resources with other living things.

- Growth is not sustainable.

- Humans are a part of nature.

- Humans are affected by natural laws.

- Humans succeed best when they maintain the integrity of natural processes sand cooperate with nature.

For example, if a fuel shortage occurs, how can the problem be solved in a way that is consistent with a sustainable ethic? The solutions might include finding new ways to conserve oil or developing renewable energy alternatives. A sustainable ethic attitude in the face of such a problem would be that if drilling for oil damages the ecosystem, then that damage will affect the human population as well. A sustainable ethic can be either anthropocentric or biocentric (life-centered). An advocate for conserving oil resources may consider all oil resources as the property of humans. Using oil resources wisely so that future generations have access to them is an attitude consistent with an anthropocentric ethic. Using resources wisely to prevent ecological damage is in accord with a biocentric ethic.

The ecological footprint (EF), developed by Canadian ecologist and planner William Rees, is basically an accounting tool that uses land as the unit of measurement to assess per capita consumption, production, and discharge needs. It starts from the assumption that every category of energy and material consumption and waste discharge requires the productive or absorptive capacity of a finite area of land or water. If we (add up) all the land requirements for all categories of consumption and waste discharge by a defined population, the total area represents the Ecological Footprint of that population on Earth whether or not this area coincides with the population’s home region.

Land is used as the unit of measurement for the simple reason that, according to Rees, “Land area not only captures planet Earth’s finiteness, it can also be seen as a proxy for numerous essential life support functions from gas exchange to nutrient recycling … land supports photosynthesis, the energy conduit for the web of life. Photosynthesis sustains all important food chains and maintains the structural integrity of ecosystems.”

What does the ecological footprint tell us? Ecological footprint analysis can tell us in a vivid, ready-to-grasp manner how much of the Earth’s environmental functions are needed to support human activities. It also makes visible the extent to which consumer lifestyles and behaviors are ecologically sustainable calculated that the ecological footprint of the average American is – conservatively – 5.1 hectares per capita of productive land. With roughly 7.4 billion hectares of the planet’s total surface area of 51 billion hectares available for human consumption, if the current global population were to adopt American consumer lifestyles we would need two additional planets to produce the resources, absorb the wastes, and provide general life-support functions.

The precautionary principle is an important concept in environmental sustainability. A 1998 consensus statement characterized the precautionary principle this way: “when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically”. For example, if a new pesticide chemical is created, the precautionary principle would dictate that we presume, for the sake of safety, that the chemical may have potential negative consequences for the environment and/or human health, even if such consequences have not been proven yet. In other words, it is best to proceed cautiously in the face of incomplete knowledge about something’s potential harm.

Environmental Justice

Environmental Justice is defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. It will be achieved when everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.

During the 1980’s minority groups protested that hazardous waste sites were preferentially sited in minority neighborhoods. In 1987, Benjamin Chavis of the United Church of Christ Commission for Racism and Justice coined the term environmental racism to describe such a practice. The charges generally failed to consider whether the facility or the demography of the area came first. Most hazardous waste sites are located on property that was used as disposal sites long before modern facilities and disposal methods were available. Areas around such sites are typically depressed economically, often as a result of past disposal activities. Persons with low incomes are often constrained to live in such undesirable, but affordable, areas. The problem more likely resulted from one of insensitivity rather than racism. Indeed, the ethnic makeup of potential disposal facilities was most likely not considered when the sites were chosen.

Decisions in citing hazardous waste facilities are generally made on the basis of economics, geological suitability and the political climate. For example, a site must have a soil type and geological profile that prevents hazardous materials from moving into local aquifers. The cost of land is also an important consideration. The high cost of buying land would make it economically unfeasible to build a hazardous waste site in Beverly Hills. Some communities have seen a hazardous waste facility as a way of improving their local economy and quality of life. Emelle County, Alabama had illiteracy and infant mortality rates that were among the highest in the nation. A landfill constructed there provided jobs and revenue that ultimately helped to reduce both figures.

In an ideal world, there would be no hazardous waste facilities, but we do not live in an ideal world. Unfortunately, we live in a world plagued by rampant pollution and dumping of hazardous waste. Our industrialized society has necessarily produced wastes during the manufacture of products for our basic needs. Until technology can find a way to manage (or eliminate) hazardous waste, disposal facilities will be necessary to protect both humans and the environment. By the same token, this problem must be addressed. Industry and society must become more socially sensitive in the selection of future hazardous waste sites. All humans who help produce hazardous wastes must share the burden of dealing with those wastes, not just the poor and minorities.

Indigenous People

Since the end of the 15th century, most of the world’s frontiers have been claimed and colonized by established nations. Invariably, these conquered frontiers were home to people indigenous to those regions. Some were wiped out or assimilated by the invaders, while others survived while trying to maintain their unique cultures and way of life. The United Nations officially classifies indigenous people as those “having an historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies,” and “consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories or parts of them.” Furthermore, indigenous people are “determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations, their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.” A few of the many groups of indigenous people around the world are: the many tribes of Native Americans (i.e., Navajo, Sioux) in the contiguous 48 states, the Inuit of the arctic region from Siberia to Canada, the rainforest tribes in Brazil, and the Ainu of northern Japan.

Many problems face indigenous people including the lack of human rights, exploitation of their traditional lands and themselves, and degradation of their culture. In response to the problems faced by these people, the United Nations proclaimed an “International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People” beginning in 1994. The main objective of this proclamation, according to the United Nations, is “the strengthening of international cooperation for the solution of problems faced by indigenous people in such areas as human rights, the environment, development, health, culture and education.” Its major goal is to protect the rights of indigenous people. Such protection would enable them to retain their cultural identity, such as their language and social customs, while participating in the political, economic and social activities of the region in which they reside.

Despite the lofty U.N. goals, the rights and feelings of indigenous people are often ignored or minimized, even by supposedly culturally sensitive developed countries. In the United States many of those in the federal government are pushing to exploit oil resources in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge on the northern coast of Alaska. The “Gwich’in,” an indigenous people who rely culturally and spiritually on the herds of caribou that live in the region, claim that drilling in the region would devastate their way of life. Thousands of years of culture would be destroyed for a few months’ supply of oil. Drilling efforts have been stymied in the past, but mostly out of concern for environmental factors and not necessarily the needs of the indigenous people. Curiously, another group of indigenous people, the “Inupiat Eskimo,” favor oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Because they own considerable amounts of land adjacent to the refuge, they would potentially reap economic benefits from the development of the region.

The heart of most environmental conflicts faced by governments usually involves what constitutes proper and sustainable levels of development. For many indigenous peoples, sustainable development constitutes an integrated wholeness, where no single action is separate from others. They believe that sustainable development requires the maintenance and continuity of life, from generation to generation and that humans are not isolated entities, but are part of larger communities, which include the seas, rivers, mountains, trees, fish, animals and ancestral spirits. These, along with the sun, moon and cosmos, constitute a whole. From the point of view of indigenous people, sustainable development is a process that must integrate spiritual, cultural, economic, social, political, territorial and philosophical ideals.

Conclusion

The preceding chapters have described how humans have both affected and been affected by the Earth system. Over the next century, human society will have to confront these changes as the scale of environmental degradation reaches a planetary scale. As described throughout this course, human appropriation of natural resources—land, water, fish, minerals, and fossil fuels—has profoundly altered the natural environment. Many scientists fear that human activities may soon push the natural world past any number of tipping points—critical points of instability in the natural Earth system that lead to an irreversible (and undesirable) outcome. This chapter discusses how environmental science can provide solutions to some of our environmental challenges. Solving these challenges does not mean avoiding environmental degradation altogether, but rather containing the damage to allow human societies and natural ecosystems to coexist, avoiding some of the worst consequences of environmental destruction.

Environmental science cannot predict the future, as the future depends on technological and economic choices that will be made over the next century. However, environmental science can help us make better choices, using everything we know about the Earth system to anticipate how different choices will lead to different outcomes.