1 Chapter 1 (College Rhetoric)

Overview

Rhetoric is a very old subject, one of the first studied in a college or university setting. However, it was not studied in terms of writing papers. It was instead studied in terms of knowing how other people could be persuaded. Such study also helped the students understand how and why they believed things, too. In this way, studying rhetoric helped prevent the spread of misinformation, because it asked people to ponder why they believed things, not to simply repeat what they believed.

While the basic role of rhetoric is covered in most Composition I classes, it’s worth reviewing the basics. If nothing else, it’s worth remembering that the teachers assigning college work are themselves “others” who must be persuaded to reward that work with good grades, and that workplaces have supervisors receiving written documents who must be persuaded that the employees are doing good work.

Note that many forms of writing are about self-expression. Poetry, journaling, and even personal narratives focus on the self. Those are different genres than most college essays. Figure out what your teacher wants to see (the reason for the assignment) and put that in the paper, because it’s the teacher’s impression of the document that matters.

Most first-year composition textbooks dealing with argumentation are based on either an analytic model (e.g. the Toulmin model) or a mode-form generative model (e.g. persuasive, narrative, and information modes). Both types deal with categorization. They essentially ask students to learn a set of categories and to then match up future writing projects by these categories.

Besides long-term pedagogical concerns, such an approach is difficult for students and teachers alike. Students have trouble seeing fine distinctions between types,

Writing For Others

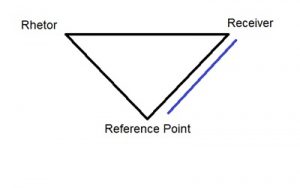

Most rhetoric is not self-centered expression. What that means is that rhetoric tries to understand what the receiver already knows, and what common reference points the different possible receivers have for any topic. Then, the rhetor (the person who is speaking, writing, or otherwise communicating) uses those two points of reference to frame the rest of the discussion. The diagram below shows that this means that the least important aspect is then what the rhetor thinks, feels, or believes.

That doesn’t mean that the rhetor’s opinion doesn’t matter. It means that the rhetor’s opinion does not make it into the communications act.

That doesn’t mean that the rhetor’s opinion doesn’t matter. It means that the rhetor’s opinion does not make it into the communications act.

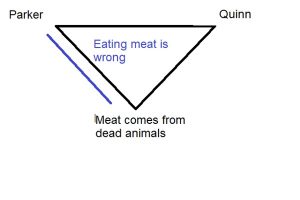

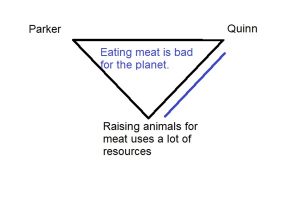

For example, Parker thinks that animals have feelings and rights just like people. Quinn doesn’t care about animals’ feelings, but Quinn does care about water pollution and energy conservation. Which of these two approaches is more likely to be effective?

Regardless of which one matches Parker’s feelings more, the one on the right is more likely to be persuasive to Quinn. Parker might care have chosen to talk to Quinn about eating meat because of a concern over animals. Parker focuses on Quinn’s concern over the planet, though, as a more effective persuasion strategy.

College Essays are Work: Very few college students wake up in the morning desperate to write an essay. Instead, they write essays because they are assignments that have been given to them by others. Likewise, very few college teachers assign essays because they look forward to spending hours grading them. Instead, they ask for essays because they are looking for students to demonstrate that they have learned something new about a subject and have thought about it at a deeper level than could be shown with a simpler examination format, like a short-answer question or a multiple choice test. In other words, college essays are not about what students “want” to say, they are about what students need to demonstrate.

This has parallels in a non-academic or “real-world” context. It is possible that some students will end up in work environments that allow them a great deal of freedom in how they do their jobs, and many jobs will reward innovation, if it’s put forward within the structure of the workplace. However, typical workplaces expect employees to arrive on-time, to conform to workplace standards, and to document everything carefully.

If you think that failing an assignment for an error is a harsh penalty, imagine dosing medicine incorrectly by a misplaced decimal point, or failing to submit a legal permit correctly for a new building being designed, or any of dozens of non-academic failures. Following “some” of the requirements is frequently similar to putting out “some” of the fire or paying “some” of you bills. The results are going to be disappointing or frustrating for everyone.

Some of the requirements of certain assignments might seem silly, but many times there is a reason behind the procedure. Even if there is not, there is value in learning how to follow a procedure for its own sake.

Failing a Paper is Easy: There are common mistakes that students make as they transition from high school-level writing to college-level writing. The most common mistakes involve students who think that their unsupported opinions matter to anyone besides those who have a personal interest in them. In early writing, it’s okay to base ideas on opinion, because simply developing ideas is the skill being learned, and writing that development out is what needs practice. That is no longer enough for an academic argument. Likewise, students frequently stumble when they believe that they don’t have to cite “stuff I already know” or “common knowledge.” In short, do not do what you always did before!

Many of you have learned different citation systems or formatting guidelines. Always check with your new teacher (and with each new assignment) to be sure that you are doing the work that is being asked of you. Do not assume that because you had a teacher who loved really imaginative introductions, that an analysis on the factors of climate change needs theme music and a romantic subplot.

Adapt! The author of this textbook once had a former student complain that she had written a paper exactly as she had been, yet she still got an ‘F’. At the very top of the assignment was a note from that teacher telling students that work that was turned in double-spaced would fail. She had double-spaced. Instructions Matter

Do not do work that is like the assignment, do the assignment. If a teacher assigns a 10-page, 8-source paper using at least two historical references, then a 7-page, 6-source paper with one historical reference is not “close enough.” If the teacher asks for an analysis of a piece of literature comparing it to the movie adaptation, do not write a review of the movie.

Frequently, students will have learned “persuasive” papers (or “informative” papers, or whatever). They will then see an assignment asking for an argument and think “ooh, I know how to write a persuasive paper.” What comes in is then a great middle-school level persuasive essay, not a college-level argument. Do not assume that because your brother is an English major and you published a short story two years ago that you have the right to ignore requirements.

Do not think that nobody has ever had your particular insight before, or that it is obvious that your argument stands without support. Do not think that “my last teacher didn’t care about this” means it’s okay to ignore the formatting requirements for submissions.

If some of this is different from English 101, that’s okay! You learn new stuff in trigonometry even after you’ve passed algebra. This is a new class with more advanced material. If you’re taking an algebra class, you cannot reasonably expect to use your long division skills and get an A. The same “paper” skills that got a ‘B’ in high school will not earn a passing grade in college, any more than kindergarten writing skills merit a passing grade in middle school.

Burden of Proof

In academic writing and college-level arguments, intuition and opinion are not enough to establish validity. It is not enough for someone to say “This might be true,” or “We don’t know this isn’t the explanation.” Instead, the person making the suggestion has to prove that there is evidence in favor of his or her suggestion being valid.

The notion of burden of proof is both among the most familiar to student writers and among the most difficult to grasp. For the most part, student writers will find that the burden of proof is on them, meaning that if they want someone to believe a claim, they must provide evidence to support that claim. The burden of proof, or the requirement to provide evidence, is always on the person seeking to prove a claim or change the status quo.

- Basically, any claim requires evidence to support it.

- Without evidence, the status quo (the assumption about how things are) is that the claim is unproven.

Think about the concept that someone is “innocent until proven guilty.” This statement implies the status quo (innocent) and it tells us who has the burden of proof (the person claiming the suspect is guilty). Note that it is possible to be “right” without meeting the burden of proof. However, a chance of being correct is not the same thing as having a valid argument.

Failing to meet the burden of proof does not mean the claim is untrue—it means that the claim is rejected until such time as the burden is met. For academic settings, the principle of a falsifiable argument is an essential tool. Evidence is presented and weighed before a conclusion is reached.

Academic arguments must meet the burden of proof for a simple reason: the inability to prove a negative. A specific claim can be falsified. For example, a claim that the arrowhead I found in my backyard is a prehistoric artifact can be examined and found to be lacking. Perhaps the arrowhead is made of the wrong materials, has signs of modern machining, or simply isn’t an arrowhead at all but rather an odd piece of rock that just looks like an arrowhead. However, this falsification does not prove that there are no prehistoric artifacts in my backyard.

If your paper relies on facts that “everyone knows”, then why does it exist? If the only thing needed to change my mind is observing things that are common knowledge, then why isn’t my mind already changed?

Explain Every Step: A developed argument does more than simply state a few facts or make a few observations. It “shows its work” like a math problem, guiding the reader through a chain of logical proof. Writers do not get to assume that they are right. Instead, they have to earn the respect of their readers. Student writers need to be careful that they do not trust information sources that act as if they are above the need for evidence, as well. Avoid making and trusting arguments that assume a position is true without evidence or justification.

Adapt to the Situation: It is unlikely that students will be able write only essays with exactly five paragraphs in every class. The five-paragraph essay is a great early tool, but it doesn’t fit longer, developed writing. Complex ideas can stretch across multiple paragraphs. The world won’t end.

It’s Not Self-expression: Some forms of writing are about self-expression. Writers should consider the reasons that others might disagree with them and then construct an argument using evidence and support.

Layering Sources: In an ideal scenario, students do not simply use sources one way (e.g. paraphrasing) or one at a time (e.g. a paragraph per source). Instead, students use sources to support or explain one another, and they quote or paraphrase as works best for the argument being made.

Parts of an argument

The primary claim is the central idea on which the rhetor is attempting to change the minds of the receivers. Often, a primary claim is called a thesis statement, although not every thesis-based approach is created equal. In academic writing, ideally, the primary claim emerges only after research has been done and the student knows what evidence is available. This is because the argument should be the conclusion of the critical thinking process.

- Primary claim: Birds are dinosaurs

A supporting claim is any argument that, if accepted, will make it easier to prove the primary claim. Sometimes, this involves making a distinct argument that only helps to prepare an audience. More often, it involves establishing a piece of fact (also see evidence) or advocating for a judgment of value.

- Supporting claim 1: birds possess anatomical features possessed only by birds and theropod dinosaurs.

- Supporting claim 2: multiple transitional fossils exist showing the development of birds from theropod dinosaurs.

Often, background statements are observations of the status quo that most people will take as a given. They might still need to be cited, but they are not likely to cause resistance among readers.

- Background statement 1: Dinosaurs first evolved millions of years ago.

- Background statement 2: Roughly 65 million years ago, many dinosaurs went extinct.

- Background statement 3: Birds are alive today.

An elaboration happens when a writer adds additional information that explains another sentence, typically by changing the way the same subject has been addressed, or by adding detail.

- Elaboration 1: some shared anatomical features of birds and theropod dinosaurs are hollow bones, the wishbone structure, and the hip socket.

- Elaboration 2: the Archaeopteryx contains obviously dinosaur-like features including teeth and a tail while also including bird-like features including feathers and wings.

Concessions happen when a writer does not want to make every argument all at once. Sometimes, a concession gives ground, admitting that there might be a limitation to the argument (e.g. even if I need to eat my broccoli, that doesn’t mean I have to like it).

- Concession 1: there are many dinosaurs that have very little in common with birds

- Concession 2: many of the older depictions of dinosaurs made them seem more like crocodiles than birds

Putting it all together

Here are the basic components of an argument assembled around a single topic.

| Dinosaurs first evolved millions of years ago, but 65 million years ago, they seem to have disappeared from the fossil record. | Background statement(s) |

| However, they did not disappear entirely, because some dinosaurs are alive today. | Primary claim (different than in the draft, because the original version is now an elaboration, or simplified form of the same concept). |

| This is because birds are dinosaurs. | Elaboration |

| Specifically, they are a kind of dinosaur called theropods, and this makes a Tyrannosaurus rex more related to a chicken than a Triceratops. | Elaboration |

| One way this can be proven is by considering the bones of these animals. | Elaboration |

| Birds possess anatomical features possessed only by birds and theropod dinosaurs. | Supporting claim |

| Some shared anatomical features of birds and theropod dinosaurs are hollow bones, the wishbone structure, and the hip socket. | Elaboration |

| While it is possible that sharing one or two of these traits might be a coincidence, | Concession |

| more than 80 shared characteristics, some unique to the two groups, exist | Elaboration |

| Likewise, multiple transitional fossils exist showing the development of birds from theropod dinosaurs. | Supporting claim |

| For example, the Archaeopteryx contains obviously dinosaur-like features including teeth and a tail while also including bird-like features including feathers and wings. | Elaboration |

| Other species, like Sinosauropteryx, help to show the development of feathers. | Elaboration |

| While the fossil record is far from complete, | Concession |

| the volume of evidence suggests that birds are dinosaurs adapted over time to a new lifestyle. | Elaboration |

Obviously, this is far from a complete argument. However, these basics should demonstrate how these components work together to complete a developed argument. College-level writing requires that students build such “proofs” by adding together all of the steps, not just some of them, and “showing the work” of both having evidence and of responding to what a receiver needs to (or wants to) know about the topic.